La Llorona, Baba Yaga, Churail: Every Culture Warns You About Her

One night, my Taya (uncle) and I were driving back from Bahria Town, Karachi. It was stupid o’clock, like 1:30 a.m., and just our luck, the tire blew out in the middle of the highway.

We pulled over on one of those endless, dusty patches with zero lights and even less civilization. While he got out to change the tire, I sat there—nervously glancing at the side mirror, the rearview mirror, my Taya, my own reflection—basically on edge for no good reason (except every reason). Then my Taya looked at me, grinning, and said, “Agar koi aurat aaye na, paer dekh lena. Ulte huay toh churail hogi.”

(“If a woman shows up, look at her feet. If they’re backwards, it’s a churail.”)

I didn’t even laugh. I just locked the car door and stared harder into the darkness like I was preparing for a Pokémon battle with the undead.

It’s funny… but also, it’s not. Because that one image—a woman in white with backward feet lurking near a forest or a road—is so deeply rooted in South Asian horror lore that even grown men joking about it do a double-take if they actually see a woman walking alone at night.

In South Asian folklore, the churail is usually a spirit wronged—maybe abused, maybe dead, or maybe betrayed. She returns, twisted by rage and vengeance. Sometimes she lures men into forests, where she drains their life. Sometimes she seduces them—only to devour them or drive them mad. And sometimes, she just… exists. Watching. Waiting. Haunting the margins.

You’ll hear variations depending on where you're from. In Pakistan, the churail is often associated with desolate places—graveyards, tree lines, isolated highways. She's also known to shapeshift, sometimes appearing as an old hag, other times as a beautiful woman. But no matter how she looks, her giveaway is always the same: her feet are reversed.

It's wild how one eerie visual can survive so many generations, whispered between aunties, cousins, and Taya-jees on midnight highway adventures.

Every culture has its version of the angry, forest-dwelling, otherworldly woman. And somehow, they all come with baggage—and usually, blood.

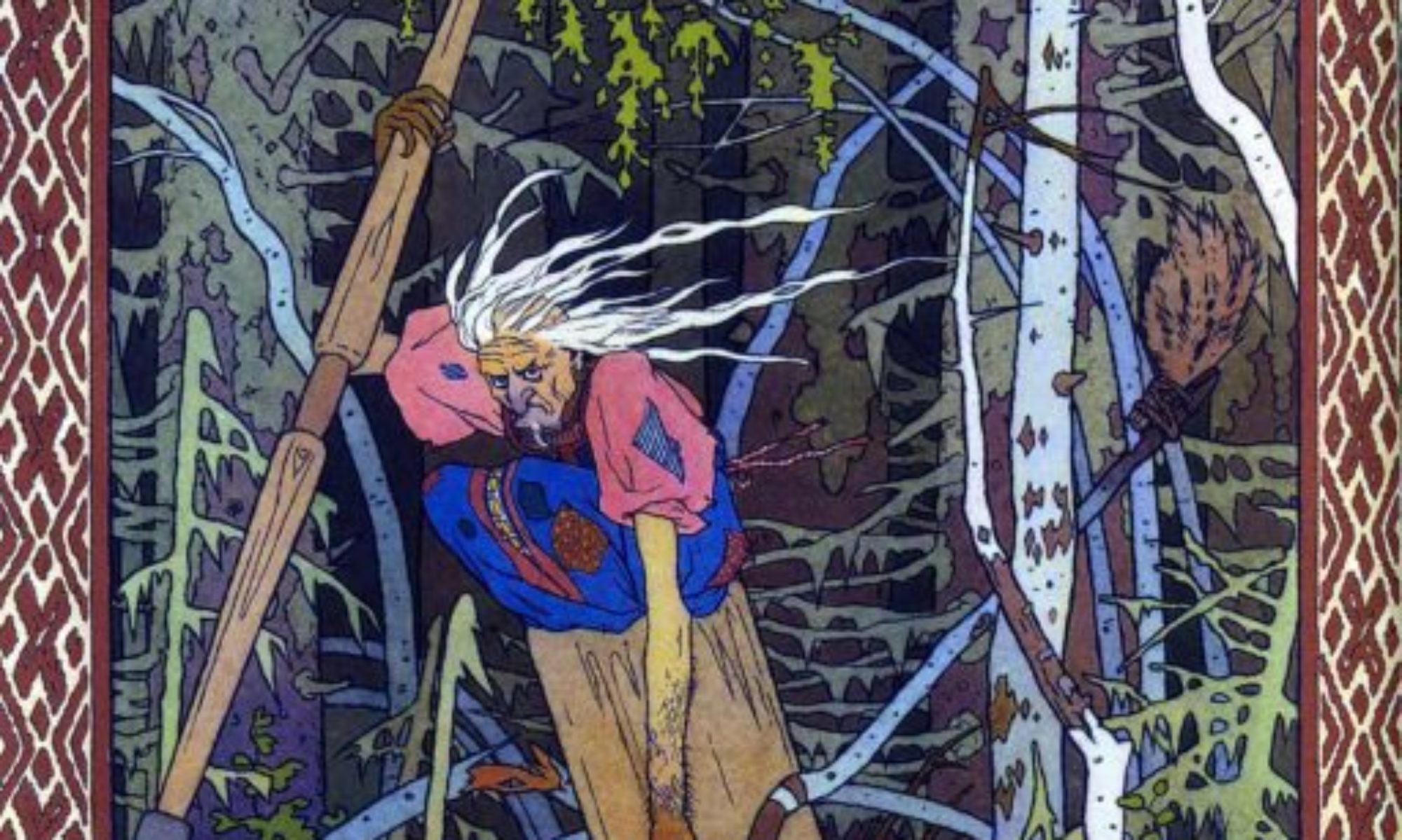

The Slavs gave us Baba Yaga—a fearsome old witch who lives deep in the woods, in a house that literally stands on chicken legs. She’s not just creepy—she’s morally chaotic. Sometimes she eats children. Sometimes she helps lost wanderers… if they’re polite and clever. Either way, she’s the keeper of ancient knowledge, independence, and unfiltered rage.

Baba Yaga doesn’t have backward feet, but she does ride around in a flying mortar and pestle, which is almost weirder.

Where the churail is often portrayed as a victim turned monster, Baba Yaga is just… a force of nature. Untamed. Wild. Respected. But feared.

Then there’s La Llorona, the Wailing Woman from Latin America. Her story cuts deep: betrayed by her husband, she drowns her children in a fit of despair or revenge (the details vary), and now she roams rivers and roads—crying, mourning, and sometimes stealing children to replace her own.

Ask any Mexican kid about La Llorona and you’ll get chills. Even if they laugh it off now, they’ll tell you not to go near the river at night. Just like we’re told not to wander into the trees during Maghrib.

So what’s the common thread here? Why do so many cultures have a scary forest lady?

Because stories like these are often cautionary tales—meant to warn you. Sometimes they warn men not to stray, or hurt women, or break vows. Sometimes they warn women not to rebel, not to wander, not to become too powerful. Other times, they’re metaphors for trauma and pain that wasn’t allowed to be expressed any other way.

The Churail, Baba Yaga, and La Llorona aren’t just villains—they’re mirrors. They reflect the fears a society has about its own treatment of women. The way these spirits target men, children, or the isolated feels intentional. Like folklore biting back.

And let's be real—when was the last time you heard about a vengeful male spirit with the same level of iconic rage aura?

Not even kidding but my Dadi used to tell me how her brother used to cycle home after work late at night near the railway quarters and once came home so scared he fainted on the doorstep

ReplyDelete